Written by Graham A. Colditz, DrPH, MD, MPH, deputy director of the Institute for Public Health; and Niess-Gain Professor in the Department of Surgery at the School of Medicine

Vice-President Biden has recently called for renewed efforts to address the burden and growing impact of cancer in the US and worldwide. Over 12 million new cases of cancer were diagnosed worldwide in 2012.

Refining strategies to implement and sustain cancer prevention interventions that are established as effective to reduce cancer incidence offers the best and fastest return on our past investment in cancer research.(1) The national Cancer Moonshot should accelerate our understanding of cancer etiology and effectiveness of treatment, and at the same time accelerate the implementation of what we know to maximize our short-term return on investment. This can be measured as lower age-specific cancer incidence (fewer cancers diagnosed) and lower age-adjusted cancer mortality. This will set us on the path to avoiding the cancer burden that is set to double in the next 30 years due to the aging US population.

What we currently know

- There are effective cancer prevention strategies, including(1):

- Colorectal cancer screening – 50% reduction colorectal cancer risk

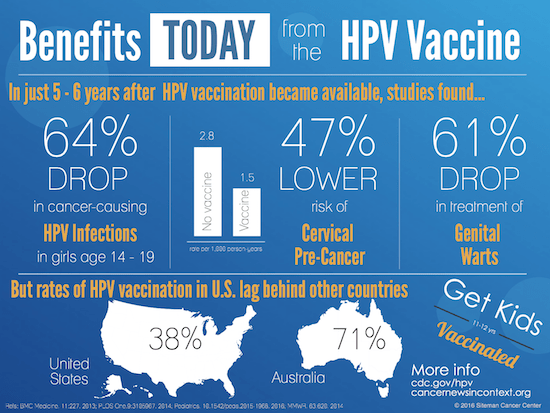

- HPV and HepB vaccines – 70 to 100% reduction cervical and liver cancer risk

- SERMs – 40 to 50% reduction in breast cancer risk

- Aspirin – 40% reduction in colon cancer risk

- Smoking cessation – 75% in lung cancer risk

- Across prevention targets, there are many persistent disparities among race/ethnic and income groups.(2, 3)

- The health care system’s general approach to cancer screening is one target at a time. As a result, only about 43% of adults are current on all recommended screenings.(4) For colorectal cancer alone, it is estimated that over 24 million adults ages 50-74 years need to be screened in the next 3 years to reach the goal of 80% population coverage by 2018.(5) The large majority of these adults are in the 50 to 64 age range and have less than a 4-year college degree.

- Rates of HPV vaccination in the US fall well below those of other childhood vaccines.

- Rates of tamoxifen and raloxifene use in women at high risk of breast cancer the US is substantially below that of those who are likely to experience a net health benefit from their use.

- Targeted system-level efforts to improve delivery of prevention services result in reduced disparities in integrated health care settings.(6,7)

One way to optimize the Moonshot Initiative would be to identify ways to increase uptake of known cancer screening and prevention strategies across all populations and design new interventions with implementation and dissemination in mind.

Some key implementation science questions

- How can discovery scientists and delivery scientists work more closely together, and so accelerate the speed of translation of research to practice?

- How to speed the uptake of effective cancer prevention strategies in community settings so they can reach populations that will benefit the most?

- Does implementation of known effective prevention and screening strategies as a cohesive integrated set of services increase their uptake, and what would the impact be on cancer outcomes?

- Do strategies that work for improving prevention services uptake and reducing disparities in integrated health systems have a similar impact when implemented in FQHC and rural health clinic settings?

- What components or organizational features of the provider setting support integrated cancer prevention service delivery?

- What is the impact of aspirin use as a broad cancer prevention strategy on cancer outcomes? What is the prevalence of bleeding and other side effects when aspirin is used at the population level, following an effective shared decision-making process?

- What impact does the broader use of preventive medications, like tamoxifen and raloxifene in high-risk women have on population outcomes for breast cancer 8? How can we speed uptake of preventive medications at the population level following an effective shared decision-making process?

- What models of smoking cessation service delivery are effective in the cancer care context? How can NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers leverage their leadership to broaden cessation programs? And what impact has Medicaid expansion had on rates of cessation and cancer outcomes?

- How do different population groups perceive cancer precision medicine approaches, and what are the barriers to their uptake? How do we innovate precision medicine that is patient-centered, respectful, and responsive to individual patient preference, needs and values? How do we communicate associated and complex concepts to different groups? Do the settings that care for underserved populations have the capacity at the provider and facility levels to deliver precision medicine approaches?

Answering these questions through rigorous implementation science in multiple settings offers opportunities for widespread impact. It should also help mitigate cancer disparities and improve understanding of the requirements for adding new prevention discoveries that arise from Moonshot research.

The scientific evidence base for effective prevention interventions includes colorectal cancer screening (9), HPV and HepB vaccination, Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) use in women at high risk of breast cancer (10, 11), aspirin use, and smoking cessation.(12, 13) Evidence from Australia shows that within 5 years of implementing HPV vaccination, high-grade cervical abnormalities are significantly reduced.(14, 15)

Yet, wide disparities exist in the uptake of these prevention efforts. We know that integrated cancer prevention programs can be implemented in low resource settings.(16) And a recent analysis showed that these efforts can also be quite cost effective. This systematic review of published studies through 2013 identified some 721 cost-utility analyses applied to oncology with 12% addressing primary prevention and 17% secondary prevention and screening.(17) Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (in 2014 dollars) for primary prevention were $48,000 for breast cancer, $16,000 for cervical cancer, and cost-saving for colorectal cancer. These were each categorized as “most cost effective,” being under $50,000.

One conclusion from such findings is that the highest return on investment of resources is likely a focus on systems that improve access to, and completion of, colorectal cancer screening and treatment. The NCI-funded initiative, Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR), provides a model for a unified cancer screening process ready for broader implementation.(18)

In sum, these are implementation science questions that are consistent with the current portfolio of NCI funding. They fit squarely within NCI’s mission and offer a unique set of steps to maximize our return on investment.

References

1. Colditz GA, Wolin KY, Gehlert S. Applying what we know to accelerate cancer prevention. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(127):127rv124.

2. Steele CB, Rim SH, Joseph DA, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence and screening – United States, 2008 and 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62 Suppl 3:53-60.

3. Meyer PA, Yoon PW, Kaufmann RB, Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Introduction: CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report – United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62 Suppl 3:3-5.

4. Emmons KM, Cleghorn D, Tellez T, et al. Prevalence and implications of multiple cancer screening needs among Hispanic community health center patients. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22(9):1343-1349.

5. Fedewa SA, Ma J, Sauer AG, et al. How many individuals will need to be screened to increase colorectal cancer screening prevalence to 80% by 2018? Cancer. 2015;121(23):4258-4265.

6. Rhoads KF, Patel MI, Ma Y, Schmidt LA. How do integrated health care systems address racial and ethnic disparities in colon cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(8):854-860.

7. Ayanian JZ, Landon BE, Newhouse JP, Zaslavsky AM. Racial and ethnic disparities among enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(24):2288-2297.

8. Chen WY, Rosner B, Colditz GA. Moving forward with breast cancer prevention. Cancer. 2007;109(12):2387-2391.

9. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627-637.

10. Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Update of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 Trial: Preventing breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2010;3(6):696-706.

11. Visvanathan K, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Use of pharmacologic interventions for breast cancer risk reduction: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2942-2962.

12. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health;2014.

13. Koh HK, Sebelius KG. Ending the tobacco epidemic. JAMA. 2012;308(8):767-768.

14. Brotherton JM, Fridman M, May CL, Chappell G, Saville AM, Gertig DM. Early effect of the HPV vaccination programme on cervical abnormalities in Victoria, Australia: an ecological study. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2085-2092.

15. Gertig DM, Brotherton JM, Budd AC, Drennan K, Chappell G, Saville AM. Impact of a population-based HPV vaccination program on cervical abnormalities: a data linkage study. BMC Med. 2013;11:227.

16. Dietrich AJ, Tobin JN, Cassells A, et al. Translation of an efficacious cancer-screening intervention to women enrolled in a Medicaid managed care organization. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(4):320-327.

17. Winn A, Ekwueme D, Guy G, Neumann P. Cost-Utility analysis of cancer prenvetoin, treatment, and control. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(2):241-248.

18. Beaber EF, Kim JJ, Schapira MM, et al. Unifying screening processes within the PROSPR consortium: a conceptual model for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):djv120.