Written by Gavi Forman, BA in political science at Amherst College; participant in the 2020 Institute for Public Health Summer Research Program – Public and Global Health Abbreviated Track

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects many people in the world every day. A shocking 17.8 million deaths around the globe were attributed to CVD in 2017, demonstrating a 20 percent increase since 2007. These numbers are staggering. How can one disease end so many lives? What is CVD, this global killer? Through a seminar included in the Institute for Public Health Summer Research Program – Public and Global Health Abbreviated Track, I was fortunate to learn from Dr. Victor Davila-Roman, MD, FACC, FASE, Associate Director of the Global Health Center, an expert in the field at Washington University in St. Louis.

Dr. Davila-Roman explained that CVD is an umbrella term that encompasses hypertension, congenital heart disease, heart failure, and strokes. CVD can occur when arteries become blocked either by fatty plaque, blood clots, or the narrowing of arteries. The body will then have a more difficult task of delivering blood and oxygen to the organs – including to the heart – and this imposes serious health risks. There is no single thing that causes CVD, but there are studied risk factors that can contribute greatly. The American Heart Association reports that 80 percent of CVDs can be prevented by living an active lifestyle, eating a healthy diet, not smoking, and avoiding high blood pressure and cholesterol.

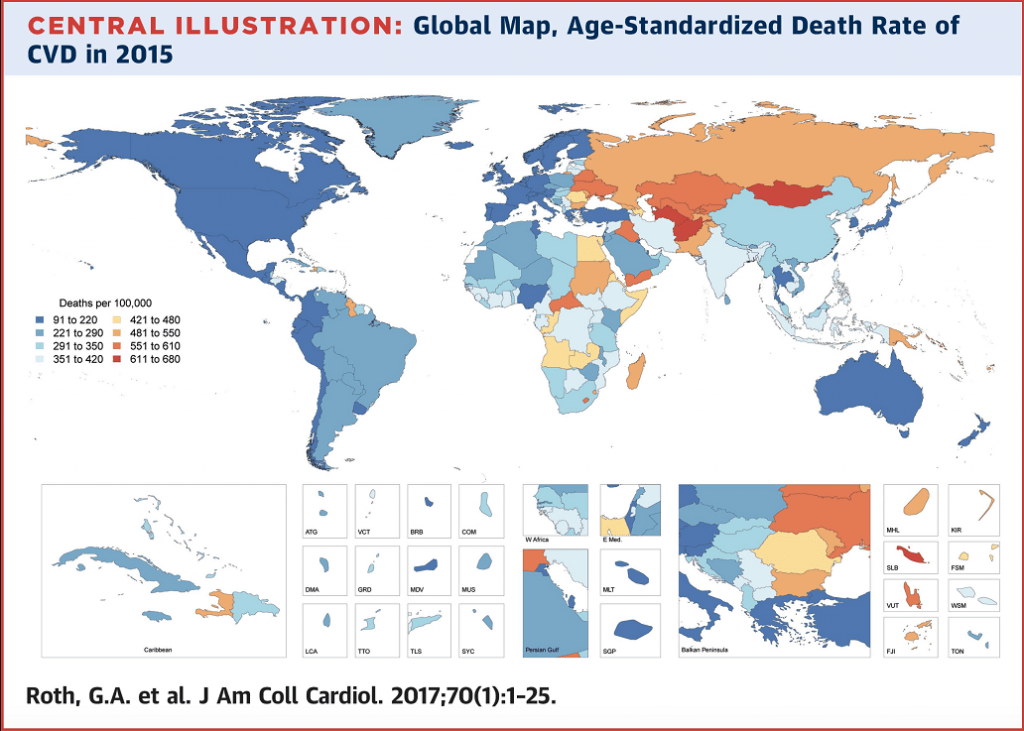

Dr. Davila particularly emphasized disparities of those affected. In low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), poverty has exacerbated the impact of CVD, and people suffer from CVD at younger ages than in high-income countries (HIC). Dr. Davila-Roman’s current research includes focus on air pollution and CVD in LMIC.

Air pollution is a large contributor to CVD. Harmful particles in the air travel into the lungs and blood and other organs and result in disrupting the body’s ability to regulate itself normally. This is a big issue in LMIC’s because many people cook over fires. They burn harmful biomass fuels (i.e. wood, dung, trash, agricultural waste) which release these harmful particles. Breathing in these dangerous fumes increases the prevalence of CVD. People in LMIC’s are also shifting to a less agrarian lifestyle: moving to cities, starting to smoke, being more sedentary. Furthermore, air pollution often goes unregulated in LMIC’s. On the same day that I heard Dr. Davila speak, the New York Times published an article on this issue of air pollution and CVD. They reported, “researchers calculate that 14 percent of all cardiovascular events and 8 percent of cardiovascular deaths are attributable to air pollution.”

Where does that leave us? As a global community, we must work to educate about CVDs, regulate air pollution, promote healthy living, and provide adequate health care.

This post is part of the Summer Research Program blog series at the Institute for Public Health. Subscribe to email updates or follow us on Twitter or Facebook.