Written by Casey Allen, MPH candidate at Saint Louis University School of Public Health and a Social Justice and Summer Pediatric Research in Global Health Translation (SPRIGHT) Scholar in the 2022 Institute for Public Health Summer Research Program

As a participant in the Institute for Public Health Summer Research Program – Public and Global Health Track, I recently attended a seminar titled, Fine Particulate Matter given by Randall Martin, PhD. Martin is a professor of energy, environmental, and chemical engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering at WashU. His presentation centered on the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 – ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages and SDG 11 – make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

All of the SDGs are broken into various targets and indicators, which help to guide and assess progress. For SDG 3, Martin focused his presentation on Indicator 3.9.1 – mortality rate attributed to household and ambient air pollution. For SDG 11, he focused on Indicator 11.6.2 – annual mean levels of fine particulate matter (e.g. PM2.5 and PM10) in cities (population weighted). Both of these indicators are centered around the concentration of fine particulate matter, specifically PM2.5.

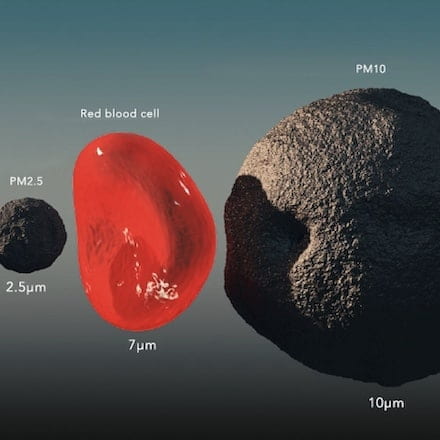

So, what is PM2.5? PM stands for “particulate matter, which is a term for a mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets found in the air, and PM2.5 refers to fine inhalable particles of which the diameter measures 2.5 micrometers and smaller (about two thirds the size of a red blood cell!).

The presence of aerosols, like PM2.5, has a wide range of implications. PM2.5 specifically has the potential to affect our health through our respiratory systems. Since the particles are so fine, they can penetrate deep into our lungs – contributing to the development of cardiovascular, respiratory, and other diseases. In fact, this exposure was estimated to have caused 4.2 million premature deaths globally in 2016. Additionally, PM2.5 exposure continues to be a major concern, with 99% of the world’s urban population breathing polluted air.

Martin posed several questions surrounding future initiatives, including: “what is needed to promote awareness of the health effects of PM2.5?” and “what steps are needed to address the SDGs on PM2.5?” For the former, we discussed the potential of personalization of PM2.5 as an individual health issue, rather than a climate- or environmentally-based one, to humanize the issue. And for the latter, the development of multidisciplinary, multi-level approaches, encompassing other fields like public health, engineering, urban planning, and policy was an overarching theme. One example of this could include the development of sustainable cities, which we heard about earlier in the program from Deborah Salvo, PhD, who spoke about the impact of large-scale modifications to the built environment (you can read more about her presentation here.) Her simulation techniques could be a helpful tool for determining the impact that a given policy may have on PM2.5 levels. While there are many potential avenues for future directions in this work, one thing is certain – progress on health outcomes will require meaningful collaboration across disciplines.