Written by Rupa Patel, MD MPH1, Nishat Rahman, PhD2, Sakila Yesmin, MPhil MSc2, Zahin Ahmed3, Razee Bazle, Hasan A. Chowdhury, Homer Venters, MD4, Ross Brownson, PhD5, Rumi Price, PhD5, Parul Bakhshi, PhD DEA6, Ali Anwar, MD7, John Crane, BA1, and Anne Glowinski, MD MPE7

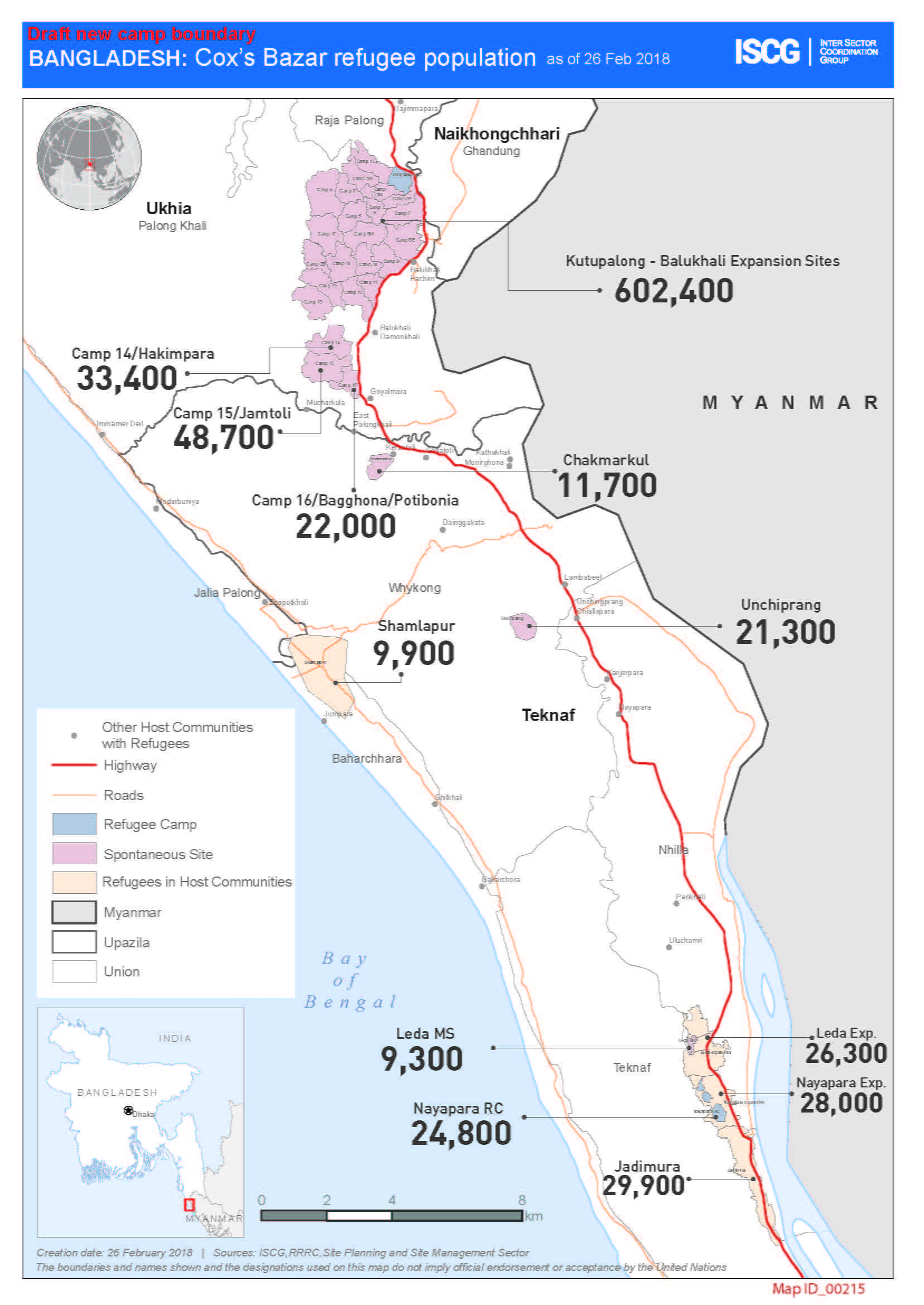

Since August 2017, over 900,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled to Bangladesh, establishing the largest single refugee camp in the world. Nearly 50% are adolescents (ages 10-18 years) and the majority is female.

Over 50% of Rohingyas have faced violence. More specifically, international reports by multiple agencies provide evidence of ethnic cleansing by the Myanmar military of the Rohingya Muslim population in the form of burning villages, performing execution-style killings, and mass rapes. For a thorough review of the history of the Rohingya population in Myanmar and their persecution, please see the article by Mahmood S, et al. (2016).

The Rohingyas are facing a myriad of problems, including statelessness (i.e., having no citizenship in any country) and a lack of essential facilities (i.e., health, schools), resources (i.e., food, water, latrines, housing), economic livelihood and physical safety. There are concurrent outbreaks of cholera, measles, and diphtheria in the context of few specialized treatment centers and a shortage of vaccines. The inciting violent events in Myanmar coupled with the daily stressors of living in the camps contribute to high levels of psychological trauma experienced by the Rohingyas. Nearly 90% of Rohingyas are estimated to have depression and 40% of them suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (Riley 2017).

These symptoms aggravate an already catastrophic situation: in their context, for instance, mothers are likely disengaged from family care tasks and younger children are listless and irritable. Lastly, despite the wide agreement of non-governmental organization (NGO) workers and international health organizations for the need to mainstream mental health concerns, age-old stigma and beliefs within the community remain an impediment.

International agencies and local Bangladeshi NGOs are providing coordinated humanitarian relief. However, there has been a severe unmet need for mental health services. Some reasons for this service delivery gap include that local NGOs are not equipped with mental health expertise or staff, Bangladeshi medical doctors and mid-level health providers (i.e., in this context, medical assistants, paramedics, and nurses) do not routinely offer nor are extensively educated on mental health assessment and treatment. Furthermore, international organizations, such as the International Office of Migration, are still adapting mental health and psychological care programs for this culturally distinct population. Further compounding the situation is that these organizations must rely on in-country medical personnel (i.e., psychiatrists, general physicians, clinical psychologists) to deliver mental health services. In addition, there is a severe national shortage of psychiatrists and clinical psychologists. Lastly, they have faced high staff turnover given the challenging work conditions. Several authors have highlighted the long-term consequences of not scaling up mental health services more rapidly (Hossein 2018, Riley 2017). However, scaling up requires a coherent and cohesive strategy built on commitment of local partners, understanding of the context and global mental health expertise.

Washington University in St. Louis faculty and trainees have been helping to address this issue by assisting local NGOs develop mental health units within their organizations and to integrate psychiatric and psychological care services within a variety of settings. These settings include child friendly centers (see pictures), women friendly centers, malnutrition units, health facilities, schools, and other sites. Global health and psychiatry faculty are conducting mental health trainings for trainers and other staff for local NGOs and have traveled to Bangladesh over the past several months. Furthermore, they have been brainstorming with Bangladeshi psychologists who have developed a cadre of community-based mental health workers on the most efficient means of scaling up these workers by other local NGOs, government sites, and humanitarian aid organizations. Increasing the uptake of this door-to-door care by Rohingyas is crucial. One method of enhancing the visibility of such services is by discussing and de-stigmatizing mental health care in the community by conducting skits in the community and other communication activities (see pictures). Faculty have advocated for incorporating mental health topics and related care into all current community-based communication initiatives that serve the Rohingyas.

The Center for Dissemination and Implementation at the Institute for Public Health harbors the expertise for advising on the integration of services in multiple settings and adapting evidence-based implementation strategies to the target setting and population (i.e., geographic location, clinics, refugees). Faculty within the center brainstormed at the WUNDIR meeting regarding the applicable frameworks for community-based mental health program adaptation for a refugee setting that is dynamically evolving. Furthermore, study areas (i.e., assessing contextual factors, interviewing stakeholder and agency heads) and methods (i.e., hybrid effectiveness-implementation designs) were outlined in order to enhance the potential rapid scale up of services while taking into account the over 900,000 Rohingyas, 10 coordinating sectors, and more than 100 implementing health partners.

During the initial response in October 2017, infectious diseases and global health faculty provided guidance for a large local NGO, who planned to serve over 50,000 Rohingyas at that time, to help their administration:

- Revise their health service protocols in order to meet the Essential Package of Services.

- Develop staff infection prevention procedures.

- Create laboratory screening and diagnostic protocols, especially pertaining to tuberculosis and HIV.

- Provide education to physicians and mid-level providers on the basics of refugee medicine.

This Essential Package of Services creates the guidelines for health clinic services and referrals in this refugee setting by the Government of Bangladesh and is adapted from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Global Health strategy and the Sphere standards. Faculty attended UNHCR-coordinated health sector meetings in Cox’s Bazaar, the nearest city to the settlement camps, to understand current protocol implementation strategies. Faculty attended meetings with the World Health Organization and the International Office of Migration to brainstorm evidence-based, multi-level strategies that may hasten sustained protocol adoption and fidelity in the context of high NGO health provider staff turnover. The health sector’s strategies for protocol implementation have been applied to other sectors and subsectors, such as mental health and psychosocial support.

Lastly, Dr. Rupa Patel, and potentially other faculty, are conducting forensic exams, as volunteers for Physician for Human Rights, among the Rohingyas to document crimes related to ethnic cleansing. Faculty will continue to train local NGO staff physicians, mid-level providers, and other trained staff to identify psychological and physical signs of torture and to refer them to treatment centers that can provide the appropriate levels of support. These initiatives foster the continued identification and documentation of violence against the Rohingyas that can aid investigations of mass crimes in an international court of law.

The next steps to address this ongoing crisis include:

- Ending the violence against the Rohingyas in Myanmar and providing adequate support for those still living in there.

- Ending statelessness for the Rohingyas living in both Myanmar and Bangladesh and for Myanmar nationality to be given to those who want to return to the country.

- Scaling up all humanitarian services for the Rohingya refugees living in Bangladesh and to have mechanisms to sustain such support for several years; this also includes the provision of services for the Bangladeshi host communities who have been affected by factors related to a rapid influx of people (i.e., economic, physical space, water/sanitation, health).

- Investigating the crimes related to ethnic cleansing and holding perpetrators accountable in the international court of law to prevent future occurrences (Beyrer 2017).

Even if some of these steps are carried out, many years of continuous care will be needed to heal psychological scars of the Rohingya refugees.

The current Rohingya crisis represents an unprecedented level of people being forced from their homes worldwide (65 million estimated by UNHCR), many whom are young children and adolescents. The Rohingyas comprise a substantial portion of the 10 million estimated to be stateless globally (UNHCR website). The denial of citizenship in any country magnifies the inability to access the basic rights of food, shelter, security, health care, education, employment and the freedom of movement. Widespread awareness of this issue is crucial to generate global advocacy to protect the dignity and rights of vulnerable populations and to ensure that crimes committed against humanity be prosecuted promptly.

For more information, visit the following websites:

- Helping the Rohingya

- BRAC

- Physicians for Human Rights

- Friends in Village Development Bangladesh

- Center for Dissemination and Implementation at the Institute for Public Health

- WUNDIR

Author Affiliations

1Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, USA

2BRAC Institute of Educational Development, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Friends in Village Development Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4Physicians for Human Rights, New York, USA

5Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, USA

6 Program in Occupational Therapy, Washington University in St. Louis, USA

7Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, USA

References

The Lancet. Our responsibility to protect the Rohingya. 2018 Dec 23;390(10114):2740.

Villasana D. Picturing health: Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Lancet. 2017 Nov 18;390(10109):2233-2242.

Hossain MM, Purohit N. Protecting the Rohingya: lives, minds, and the future. Lancet. 2017 Feb 10;391(10120): 533.

Riley A, Varner A, Ventevogel P, Taimur Hasan MM, Welton-Mitchell C. Daily stressors, trauma exposure, and mental health among stateless Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Transcult Psychiatry. 2017 Jun;54(3):304-331.

Beech H. Rohingya children facing ‘massive mental health crisis’. New York Times (New York), Dec 31, 2017. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/31/world/asia/rohingya-children-myanmar.html. Accessed Jan 2, 2018.

Human Rights Watch. Burma: satellite imagery shows mass destruction. 214 villages almost totally destroyed in Rakhine State. Sept 19, 2017. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/09/19/burma-satellite-imagery-shows-mass-destruction. Accessed Feb 21, 2018.

Beyrer C, Kamarulzaman A. Ethnic cleansing in Myanmar: the Rohingya crisis and human rights. 2017 Sep 30;390(10102):1570-1573.

Mahmood SS, Wroe E, Fuller A, Leaning J. The Rohingya people of Myanmar: health, human rights, and identity. 2017 May 6;389(10081):1841-1850.

Essential Package of Services. https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/bangladesh/health

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Figures at a glance. http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html. Accessed February 20, 2018.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. What is a refugee? https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/what-is-a-refugee/. Accessed on February 22, 2018.

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/. Accessed February 18, 2018.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Global Health strategy. http://www.unhcr.org/530f12d26.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2018.

The Sphere Project. http://www.sphereproject.org/. Accessed February 20, 2018.

UNICEF. Guidelines for Child Friendly Spaces in Emergencies. https://www.unicef.org/protection/Child_Friendly_Spaces_Guidelines_for_Field_Testing.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2018.