Written by Beth Prusaczyk, PhD, instructor in the Department of Medicine at the School of Medicine

It is hard to imagine a field of study that would not benefit from incorporating dissemination and implementation (D&I) into its strategic plan and foci. Many fields such as medicine and public health have already done so and have furthered not only their own fields but have also improved the science of D&I. However, despite encompassing a wide variety of disciplines and being routinely identified as critical areas of research, the fields of geriatrics and gerontology have yet to fully engage with D&I scientists and view challenges through the lens of D&I. And the reasons why these fields could benefit from incorporating D&I may be the same reasons why they have not fully done so.

Transdisciplinary problems

The problems facing the fields of geriatrics and gerontology are often transdisciplinary—meaning to understand and solve them they require the expertise and effort of different disciplines. Common areas of research that require a transdisciplinary effort include falls, long-term care, productive and active aging, caregiving, dementia, and readmissions. None of these issues occur in silos. They require expertise from the fields of medicine, public health, social work, nursing, occupational therapy, physical therapy, business, and others. With so many different fields working together to solve these problems, one would think there would be a strong push to ensure the solutions were implemented into routine practice or that there would be a natural progression to D&I in the research process. After all, transdisciplinary teams are required for implementation research.(1)

Yet there is very little in the D&I literature related to these issues, and perhaps the sociological phenomenon known as the “diffusion of responsibility” is to blame. The diffusion of responsibility (sometimes also referred to as the “bystander effect”) states that a person is less likely to take responsibility for action or inaction when others are present.

While this phenomenon relates to individuals, perhaps it can help to explain why critical transdisciplinary problems in geriatrics and gerontology often fail to make it to the D&I phase. Perhaps each discipline believes the implementation of the solutions is the responsibility of another. If investigators from medicine, nursing, social work, and occupational therapy work together to create an effective, system-level intervention for reducing falls, for example, who is in charge of making sure that intervention is implemented after the randomized trials are complete? Just as the solution required a transdisciplinary research effort, so will the implementation of that solution.

There are likely other factors hindering the routine implementation of transdisciplinary interventions for older adults but if the diffusion of responsibility phenomenon is partly to blame, a critical first step in mitigating its effect is for transdisciplinary teams to discuss plans for implementation at the beginning of a research project and identify a protocol for dissemination and implementation that includes all disciplines.

Funding opportunities

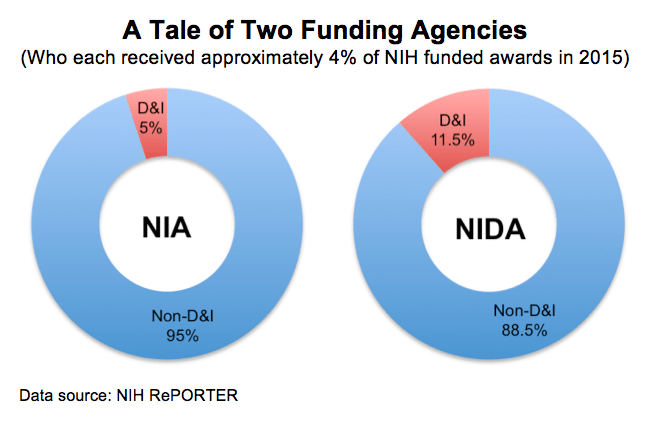

The problems facing the fields of geriatrics and gerontology are routinely identified as areas in critical need of study and consequently these areas are also relatively well funded. Among all grants awarded by the National Institutes of Health in 2015, the National Institute of Aging (NIA) received approximately 4% of awards (range: 0.3% to 14%), placing it ninth out of the 25 institutes. There is also considerable funding available for aging researchers from private foundations such as the Alzheimer’s Association, The John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Retirement Research Foundation. This level of support suggests that there is a broad recognition of the importance of aging research and the fields of geriatrics and gerontology. However, taking a closer look at this funding reveals very little support for the D&I of aging research.

A query of the NIH RePORTER, a database of funded awards, for all NIA 2015 new awards under the R, K, and F mechanisms revealed a total of 443 projects. Yet only 5% (23) of these projects had the words “dissemination” or “implementation” in the project abstract. And while this is likely an overestimate (the mere presence of these words does not necessarily indicate a true D&I project), even with this generous definition, only 5% of projects funded by the ninth-largest NIH Institute (in terms of awards) relates to D&I.

A shift in NIA priorities, including more specific calls and dedicated funding for D&I-related projects, could significantly improve the number of researchers engaged in aging-related D&I work.

Compare this to the tenth largest NIH Institute, the National Institute on DrugAbuse (NIDA), which also captured approximately 4% of the NIH’s total funds for awarded projects. NIDA awarded approximately 373 new projects in 2015 but 11.5% (43) included the words “dissemination” or “implementation” in the project abstract.

In other words, NIDA captures approximately the same (relatively large) percentage of NIH funds as NIA but funds over twice as many D&I-related studies. With considerable research funds available but little dedicated to D&I, it seems only logical that researchers in geriatrics and gerontology would focus their efforts on non-D&I projects in order to obtain funding. A shift in NIA priorities, including more specific calls and dedicated funding for D&I-related projects, could significantly improve the number of researchers engaged in aging-related D&I work.

Conclusion

The fields of geriatrics and gerontology seem primed for D&I science due to their transdisciplinary nature and considerable funding opportunities. However, these characteristics may serve as double-edged swords, simultaneously bolstering and hindering D&I science in the fields. By design, transdisciplinary research involves multiple disciplines. With so many different people involved, the “diffusion of innovation” task may fall prey to the “diffusion of responsibility” phenomenon in which everyone thinks everyone else will be responsible for ensuring the research is disseminated and implemented. Thus the transdisciplinary strength of these fields may also be hindering its D&I efforts.

Additionally, there is extensive funding available for the fields, which indicates a broad recognition of the importance of aging research. However, there is little funding offered or awarded to D&I-related research, which results in essentially a large amount of low-hanging “non-D&I” fruit for researchers to apply for. In other words, aging researchers are indirectly dis-incentivized to conduct D&I research.

This is not to say that the fields can never or will never fully embrace D&I. Two possible solutions include:

(1) transdisciplinary research teams having purposeful conversations from the beginning on who will take the lead in disseminating and implementing the results and how each discipline will contribute and

(2) shifting the funding priorities to entice more D&I-related applications and then ensuring a larger proportion of these studies are funded.

These are just two of the many necessary steps on the bridge connecting aging research to practice but without them the true potential of aging research will never be fully realized.

Reference

1. Bauer, M. S., Damschroder, L., Hagedorn, H., Smith, J., & Kilbourne, A. M. (2015). An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC psychology, 3(1), 1.